In November of last year, Minister of State for Transport John Hayes hit the headlines with his impassioned attack on Britain’s brutalist architectural legacy.

What is Brutalism?

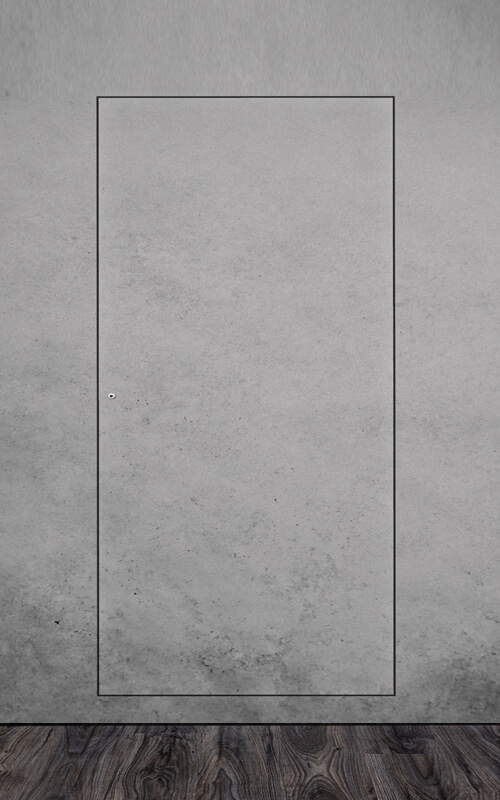

Brutalism is a post-war architectural style, defined by its rugged and rough-hewn forms. The design emphasis is placed on functionality and utility, while the preferred materials of construction are concrete and brick.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) define the five distinguishing features of brutalism as follows:

1. Unfinished surfaces

2. Uncommon shapes

3. Heavy materials

4. Huge forms

5. Small windows in relation to the overall building

The term brutalism derives not, as is often assumed, from the imposing designs of the buildings, but from the french for ‘raw concrete’: béton brut. The term was coined by Swedish architect Hans Asplund in 1950, but it was popularised by architectural critic Reyner Banham in his critiques of the work of English architects Alison and Peter Smithson who designed the soon to be demolished Robin Hood Gardens. The Smithsons were standard bearers for the brutalist movement, which rebelled against the pre-war ‘formal’ architectural style.

An optimistic style?

Brutalism in the UK was born out of a need to rebuild the war-ravaged towns and cities of the UK, quickly and efficiently. The brutalist material of choice, concrete, the second most consumed material in the world after water, was readily available, and, crucially, cheap. There was also an aesthetic desire for the ‘new’, for a style which was bold and forward thinking, and heralded a brighter future beyond post-war austerity.

Brutalism, which departed so radically from contemporary and classical architecture, and prioritised function over form, was seen for many as the perfect solution. ‘Brutalism must be taken in context’, says Jonathan Foyle, chief executive of the World Monuments Fund Britain, ‘after the war, a lot of housing was needed in a hurry, but it was designed with the best of intentions. It’s a very optimistic style.”

A monstrous carbuncle

By the 1980s brutalism had fallen out of favour with architects, while the general public had arguably made up their minds much earlier. The sheer incongruity of the designs, of the massive, imposing car parks, libraries, shopping centres and housing blocks, had become synonymous with the very thing the architecture had been deployed to transcend, the bleakness of post-war austerity.

The result was that brutalism became associated with crime, poverty and ugliness generally, and was taken to be everything that was wrong with modern architecture. Such was the antipathy to the brutalist style that Prince Charles saw fit to abandon the customary royal reserve in a 1984 speech to the Royal Institute of British Architects, in which he lambasted the towering extension to the National Theatre as ‘monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend’.

A brutalist renaissance?

In recent years, the UK’s brutalist legacy has become something of a cultural battleground, with Minister of State for Transport John Hayes the latest combatant to enter the fray. Brutalist landmarks, such as Prince Charles’ despised National Theatre have become tourist attractions in their own right. According to Dr Barnabas Calder of the University of Liverpool, author of the defence of brutalism, Raw Concrete, ‘attitudes to brutalism are certainly becoming a lot less hostile, the change is moving fast…two years ago, my pitch was to defend brutalism to a universally hostile public. Now it looks to be more of a celebratory history.’ Many brutalist buildings, formerly considered eyesores by many, are now being preserved for the nation by English Heritage. Buildings such as Preston Bus Station, Robin Hood Gardens and Sheffield’s Park Hill estate have all been the subject of protracted disputes to either preserve or demolish the buildings. Preston Bus Station and the Park Hill estate were spared the chop, but Robin Hood Gardens is set to be demolished shortly. Other buildings, such as Birmingham’s Central Library, have already fallen by the wayside.

Brutalism has never been well loved by the general population, and, with the intervention of John Hayes, it seems unlikely to come back into favour with the establishment anytime soon. Nevertheless, with the help of the English Heritage, and leading architects and critics, the artistic and cultural value of brutalism is being re-evaluated. Perhaps even the most strident critics of brutalism will concede that some of its most iconic buildings are worth preserving if only to allow future generations to make a final judgement on their value.

We'd love to hear your opinion, leave your thoughts below...

link to the image we used: https://www.wacoconcretecompany.com/